- Home

- J. T. Edson

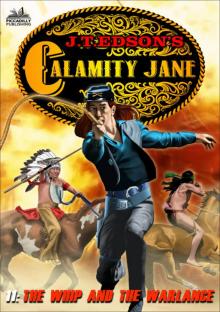

Calamity Jane 11

Calamity Jane 11 Read online

The Home of Great Western Fiction!

Having thwarted one scheme to invade Canada from the USA, Belle Boyd, the Rebel Spy, and the Remittance Kid were hunting the leaders of the plot, who had escaped and were plotting another attempt. To help them, they called upon a young lady called Miss Martha Jane Canary – better known as Calamity Jane...

Belle, Calamity and the Kid made a good team, but they knew they would need all their fighting skills when the showdown came. For they faced le Loup-Garou and the Jan-Dark, the legendary warrior maid with the war lance who, it had long been promised, would come to rally all the Indian nations and drive the white man from Canada.

THE WHIP AND THE WAR LANCE

CALAMITY JANE 11

By J. T. Edson

First published by Corgi Books in 1979

Copyright © 1978, 2020 by J. T. Edson

Published by Arrangement with the Author’s Agent

First Digital Edition: September 2020

Names, characters and incidents in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to actual events, locales, organizations, or persons living or dead is purely coincidental.

You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by means (electronic, digital, optical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

This is a Piccadilly Publishing Book / Text © Piccadilly Publishing

Visit www.piccadillypublishing.org to read more about our books

Cover illustration by Tony Masero

Series Editor: Mike Stotter

For Nicola Gibbon, a ’orrible infant and the evil spirit of my “spiritual home” the White Lion Hotel, Melton Mowbray, who assures me that she hates me more than she hates anybody else.

Author’s Note

While complete in itself the events recorded in this work continue from those which take place in THE REMITTANCE KID.

J. T. Edson

Chapter One – Maybe Reckons She’s Jan-Dark

‘They’re down in the valley, like I told you they’d be,’ Roland Boniface announced, returning to where his two companions were sitting their horses. Gathering up the dangling reins which had served to ground hitch his own mount, he slipped his right foot into the stirrup iron and swung astride the saddle. ‘But are you sure that you want to go through with this?’

‘Of course I’m sure!’ retorted Irène Beauville, at whom the question had been directed, without a moment’s hesitation. ‘Why do you think I told you to bring me here?’

‘It’s not wise!’ Jacques Lacomb protested dolefully. ‘M’sieur Cavallier won’t be pleased if anything goes wrong.’

‘Let me worry about what will, or won’t, please le Loup-Garou, Vieux Malheureux,’ Irène commanded in an imperious fashion, although she conceded to herself that – in addition to living up to his nickname ‘Old Miserable’ – the elder of her companions was making a considerable understatement in his reference to how Arnaud ‘the Werewolf’ Cavallier would react should her intentions end in disaster. Thrusting the thought aside, as she had never been one to worry about what might happen when she had put her mind to something, she shook the weapon grasped in her right hand and continued, ‘I’m the one who is going to have to use this when the time comes. So I want to be sure I’m able to.’

Although the trio on the ridge about ten miles north of the junction of the Red Deer and South Saskatchewan Rivers were speaking French, the side of the horse from which Boniface had mounted, and their appearances were more suggestive of Indian than Gallic origins. The sheaths of the knives, their belts, moccasins, and other items of attire were of Indian manufacture. ‘Medicine’ patterns made of brass tacks decorated the woodwork of the old Henry rifle resting across the crook of Lacomb’s left arm.

All three sat their wiry, smallish horses with the relaxed, effortless-seeming grace of highly competent riders. Single cinched, with high, sharply curved cantles and pommels, the saddles were almost skeletal in design and had wooden trees to which rawhide had been shrunk. The animals were controlled and guided by hackamores. With a head-piece something like a bridle, a wide browband which could be slid down to act as a blindfold and a rawhide loop – known as a bosal – around the head immediately above the mouth serving in place of a bit, these resembled an ordinary halter except for having one piece reins instead of a lead rope. Such equipment was indicative of Indian rather than European equestrianism.

That there should be suggestions of two different racial cultures was not surprising. The trio were Metis.; members of the race which had evolved in Canada – the name being a corruption of the French word, metissage, meaning miscegenation – as a result of marriages between voyageurs 1 and women belonging to the various Indian nations with whom they had come into contact.

Eldest of the three by a good twenty years, Jacques Lacomb also gave the clearest indications of possessing Indian blood as he slouched on the back of his kettle-bellied dun gelding. Short in stature, stocky of build, bareheaded, he had shoulder long straight black hair. Never pleasant or amiable, his features were aquiline, but also somewhat Mongoloid in appearance and of a deep coppery bronze pigmentation. At that moment, they were registering resentment over the disrespect shown to him by one who was only a mere woman in spite of the responsible function she had been selected to fulfil and which she was about to endanger needlessly. He wore plain, grease blackened buckskins. Only the scarlet Hudson’s Bay ‘Three Point’ blanket draped over his shoulders, the rifle and the J. Russell and Co. ‘Green River’ knife 2 in his Assiniboine Indian-made sheath were the products of the white side of his upbringing.

Tall, slender, yet wiry, Roland Boniface had light brown hair. It was just as long and straight as Lacomb’s, but emerged from beneath a round topped black bearskin cap with flaps which could be lowered to protect the ears in cold weather. Although almost as deeply tanned, his fairly handsome face had blue eyes and a moustache to make it seem more Gallic than Indian. He had on a fairly clean elkskin shirt emblazoned by red, white and blue medicine symbols, but his nether garments, ending in the calf high leggings of his Blackfoot-style moccasins, were a pair of dark blue British Army riding breeches. In addition to his ‘Green River’ knife, he carried a Colt 1860 Army revolver butt, forward in a cavalry holster, from which the flap had been cut, at the right side of his belt. The Winchester Model of 1866 carbine he was drawing from the boot of his leggy roan stallion’s saddle was unadorned.

By the standards of either race, Irène Beauville could be regarded as an exceptionally fine example of feminine pulchritude. Close to five foot eight inches in height, she was in her mid-twenties. Unlike her companions, she had her tawny almost blonde hair cut short. Less deeply tanned than either of the men, she had gray eyes and her features, while warning of her arrogant nature, had an aquiline beauty. She wore a dyed horse-hair shirt which clung to the twin mounds of her imposing bosom and slender waist in a way which showed it alone covered them. Curvaceous hips and well-muscled thighs filled the fringed buckskin trousers just as adequately. There was a Plains Cree Indian bear-claw necklace about her throat and each wrist was graced by a wide Navajo silver and turquoise bracelet. The eight-inch bladed, Alfred Hunter ‘Bowie’ knife had a fancy bone handle and German silver mountings. Although it had been made in Sheffield, England, it was no less an efficient weapon than those carried by the two men. All in all Irène’s appearance was striking as she sat straight backed and proud on the small, well-built paint gelding. However, the men of her people having strong views on the proprieties and the status of a wo

man in their society, her attire was to say the least unconventional. She had never been unduly troubled by the possibility of offending masculine susceptibilities and, being so well regarded by le Loup-Garou, she no longer needed to concern herself over whether they approved of her dress and behavior or not.

The knife was not the girl’s only armament. However, despite being decorated by a clump of eagle feathers and painted in the traditional fashion, the lance held vertically in her right hand was not the usual kind carried by Indian warriors. The diamond-section steel head was twelve inches in length and two and a half inches at its widest, tapering to an acute point. It was fastened to the sturdy nine-foot ash handle by a pair of steel languets, each thirty-six inches long and secured with five screws. Passing around her wrist, a rawhide loop was attached to the shaft at its point of balance. On the bottom of the pole was a rounded metal ‘shoe’ and, as an aid to being carried, it rested in a metal cap attached to the saddle’s off side stirrup iron.

Setting the horses moving at a slow walk, the trio rode in the direction from which Boniface had returned. After covering about half a mile, first down and then up a gentle slope, they drew rein and scanned the terrain ahead of them from the concealment of a clump of bushes. At the bottom of a flat and fairly open U-shaped valley some three hundred acres in extent was a herd of about thirty buffalo.

‘Well, there you are,’ the taller man said. ‘But going after them will be very dangerous.’

‘I’ve run buffalo before,’ Irène answered, yet her tone was just a trifle less arrogant and certain.

‘You was using a rifle and on a full village hunt,’ Boniface pointed out. ‘Setting after one alone and with only a lance is a very different kettle of fish, particularly when it’ll be one from a bunch of “settlers” like that lot. Their big boss bull won’t be frightened off by a single rider.’

‘From what I’ve heard, you’ve done it,’ Irène replied, knowing that the lanky man was an accomplished hunter and, despite her imperious nature, being sufficiently cognizant of the danger to be willing to listen to his advice. ‘So what’s the best way to go about it?’

As the girl was aware, even before the wholesale slaughter of the once enormous herds, small groups of buffalo – particularly those of the ‘wood’, Bison Bison Atliabaseae, sub-species rather than the ‘plains’ variety, B.B. would forsake the completely migratory habits which the sheer volume of numbers caused the majority of their kind to adopt in order to find sufficient food to support life. Known as “settlers”, such dissidents were invariably led by a bull of sufficient size, strength and aggressiveness to take over and defend a suitable location against all comers. Once this happened, the dominant male, whether the original or the successive leaders among his offspring developed strong territorial instincts and would not hesitate to attack on sight potential trespassers or enemies. What was more, as a full-grown bull could measure twelve feet overall and stand six feet high at the humped shoulders, with a weight of between two and three thousand pounds, it was no mean adversary when charging.

‘I don’t know what M’sieur Cavallier’s going to say when he hears about this,’ Lacomb protested miserably. ‘In fact, I shouldn’t be letting you do it.’

‘And I don’t think it’s up to you to say whether Irène can, or can’t do anything,’ Boniface answered. Although he had never seen France, the combination of his paternal Gascon and maternal Blackfoot bloodlines revolted against taking orders, or even accepting sound advice, from one born out of Provencal and Assiniboine stock. So, in spite of having no doubt what le Loup-Garou would say and might try to do if the girl should be rendered incapable of carrying out the task for which she had been training, he was goaded into supplying her with information. ‘I know you’re a damned good rider. That horse you’re on’s been trained for running buffalo with rifle, bow and lance. He’s as agile as a cat. As long as you stick on his back, the buffalo hasn’t been born that can get to you.’

‘What happens if it falls?’ the older man demanded.

‘He never has and you couldn’t knock him off his feet if you tried!’ Boniface replied indignantly.

‘And the horse hasn’t been foaled that I can’t stay on!’ Irène supplemented boastfully, but she could not stop herself thinking of what she had seen happen during a village hunt when a rider was thrown while racing alongside a fast fleeing herd of buffalo. However, her pride and hot temper would not allow her to call off the attempt after having insisted upon being brought out of their way to make it. ‘So, as he won’t fall, I’ll still be with him when he catches up to them.’

‘That’s something else,’ Boniface went on, while Vieux Malhuereux scowled his disapproval. ‘If you go down there yelling as loud as you can, they’ll take off along the valley bottom because that’s the easiest going—’

‘Fine,’ Irène said eagerly. ‘That will make it easier for me—’

‘Not entirely,’ Boniface contradicted, beginning to wish he had pretended he could not locate the “settlers.” As it was, he knew the only hope was for him to alert the headstrong girl to all the dangers she would be likely to encounter. ‘The rest will take off all right, but not the big boss bull. His kind don’t scare one little damned bit and he’ll be coming to meet you. That’s when you’ll really have to watch your riding. The paint knows what to do. He’ll swerve around the bull at the last moment and keep on after the others. And that’s what you do, keep going. Don’t slow down, because he’ll be round and chasing you as fast as he can when he sees you’re running his herd. Pick the one you want and let the paint know which it is. He’ll keep you by it. Then use the lance the way you’ve learned and then get the hell out of there even faster than you went in or the big boss will have you.’

For a few seconds, Irène sat committing all she had been told to memory. Then she sucked in a deep breath, grasped the reins more tightly with her left hand and set her feet securely in the stirrups. Having done so, sensing that her companions were studying every move she made and wanting to avoid letting them know her misgivings, she gave the signal for the paint to advance. As it did so and started to pass around the edge of the bushes, she lowered the lance to the horizontal and tucked the handle firmly between her right forearm and ribs. With that accomplished, she kicked her heels against the horse’s sides.

Realizing what was wanted from it, the little paint increased its speed even though it was approaching a slope which was fairly steep and covered in many places by patches of shale-like gravel. Instead of holding back, it continued thrusting with its hind legs and sending sprays of the small rock fragments flying to the rear.

Grazing about four hundred yards below, as yet the buffalo were unaware of the intruders. Watching them and concentrating upon remaining aboard the paint, Irène found her worries disintegrating and was filled with a growing sensation of wild exhilaration. Although she would be using a different, more impressive animal for the work that lay ahead, she had already formed a rapport with the little horse. Before they had gone many feet, she had sufficient confidence to let it have its head and found it needed no guiding, but headed straight for the herd.

‘We should go after her!’ Lacomb declared, gesturing with the Henri on his left arm. ‘A lance isn’t a fit weapon to use against buffalo.’

‘Us Blackfoots do it regular,’ Boniface answered, although much the same idea had occurred to him. ‘And, like she said, when the time comes she’s going to have to know how to use the lance. If she puts down one of them, there’ll be no doubt she can.’

Wild with excitement, Irène still remembered the advice she was given prior to setting off. The screech she gave might lack the resonance of an Indian brave’s war whoop, but it produced the desired effect. Almost too successfully, in fact. Hearing the cry, the paint clearly concluded it was made as a signal for extra speed and accelerated with such force that the girl was pressed against the saddle’s high cantle.

Twice more Irène yelled. On each occasion, she felt the

little horse quiver and increase the pace of the descent. Starting to rush across the level ground at the foot of the slope, she saw the herd was stampeding along the valley about a hundred yards away as Boniface had said they would. He had been just as accurate in his summation of how the dominant bull would respond to the invasion of its territory. Instead of fleeing with the others, it was already about halfway between them and the intruders, charging with every intention of pressing home the attack.

Despite her exhilaration, the girl felt a sense of awe as she watched the enormous beast rushing ever closer under the impetus of their combined speeds. She tightened her legs around the paint’s body and grasped the reins until her knuckles showed white as she prepared to retain her seat through what she knew would be a sudden and violent change of direction.

Thirty yards separated Irène from the bull!

Twenty!

Ten!

For a terrifying moment, the girl thought the horse was acting in panic and meant to meet the gigantic approaching beast head on.

Uttering a whistling sound as loud and shrill as the noise made by high pressure steam bursting from a locomotive, the bull lowered his shaggy head and his short tail became as stiff as a poker, the very hairs of the tassel at its tip seeming to stand erect. He was preparing to drive home the stout, outward and upward curved horns which seemed to Irène to be of far greater size than their actual twenty-three inches of length and seventeen inches circumference around the base.

Timing the move perfectly, the paint gelding justified Boniface’s confidence. As the bull prepared to launch the attack, it swerved to the left. Only slightly, but sufficient to avert the collision. Irène was carried by the huge beast so close that she could have kicked him in the ribs while passing.

Calamity Jane 11

Calamity Jane 11 The Floating Outift 33

The Floating Outift 33 Cap Fog 5

Cap Fog 5 The Floating Outfit 34

The Floating Outfit 34 The Code of Dusty Fog

The Code of Dusty Fog The Floating Outfit 21

The Floating Outfit 21 The Floating Outift 36

The Floating Outift 36 Calamity Jane 2

Calamity Jane 2 Calamity Jane 6: The Hide and Horn Saloon (A Calamity Jane Western)

Calamity Jane 6: The Hide and Horn Saloon (A Calamity Jane Western) Waco 7

Waco 7 The Floating Outfit 25

The Floating Outfit 25 Waco 7: Hound Dog Man (A Waco Western)

Waco 7: Hound Dog Man (A Waco Western) The Floating Outfit 47

The Floating Outfit 47 The Floating Outfit 42: Buffalo Are Coming!

The Floating Outfit 42: Buffalo Are Coming! The Floating Outfit 46

The Floating Outfit 46 Dusty Fog's Civil War 11

Dusty Fog's Civil War 11 The Floating Outfit 61

The Floating Outfit 61 The Owlhoot

The Owlhoot Alvin Fog, Texas Ranger

Alvin Fog, Texas Ranger The Floating Outfit 34: To Arms! To Arms! In Dixie! (A Floating Outfit Western)

The Floating Outfit 34: To Arms! To Arms! In Dixie! (A Floating Outfit Western) The Floating Outfit 44

The Floating Outfit 44 Dusty Fog's Civil War 10

Dusty Fog's Civil War 10 Calamity Jane 10

Calamity Jane 10 Cap Fog 4

Cap Fog 4 The Floating Outfit 51

The Floating Outfit 51 The Floating Outfit 50

The Floating Outfit 50 The Floating Outfit 49

The Floating Outfit 49 The Floating Outfit 10

The Floating Outfit 10 Apache Rampage

Apache Rampage The Floating Outfit 15

The Floating Outfit 15 Ranch War

Ranch War The Floating Outfit 11

The Floating Outfit 11 The Devil Gun

The Devil Gun Sacrifice for the Quagga God (A Bunduki Jungle Adventure Book 3)

Sacrifice for the Quagga God (A Bunduki Jungle Adventure Book 3) Comanche (A J.T. Edson Western Book 1)

Comanche (A J.T. Edson Western Book 1) The Floating Outfit 48

The Floating Outfit 48 Wacos Debt

Wacos Debt The Rebel Spy

The Rebel Spy Cap Fog 3

Cap Fog 3 Trouble Trail

Trouble Trail Cold Deck, Hot Lead

Cold Deck, Hot Lead Rockabye County 4

Rockabye County 4 The Bullwhip Breed

The Bullwhip Breed Set Texas Back On Her Feet (A Floating Outfit Western Book 6)

Set Texas Back On Her Feet (A Floating Outfit Western Book 6) The Floating Outfit 25: The Trouble Busters (A Floating Outfit Western)

The Floating Outfit 25: The Trouble Busters (A Floating Outfit Western) Fearless Master of the Jungle (A Bunduki Jungle Adventure

Fearless Master of the Jungle (A Bunduki Jungle Adventure Wanted! Belle Starr!

Wanted! Belle Starr! The Big Hunt

The Big Hunt Running Irons

Running Irons The Floating Outfit 19

The Floating Outfit 19 You're in Command Now, Mr Fog

You're in Command Now, Mr Fog The Floating Outfit 27

The Floating Outfit 27 Texas Killers

Texas Killers Ole Devil and the Mule Train (An Ole Devil Western Book 3)

Ole Devil and the Mule Train (An Ole Devil Western Book 3) Bunduki and Dawn (A Bunduki Jungle Adventure Book 2)

Bunduki and Dawn (A Bunduki Jungle Adventure Book 2) The Fortune Hunters

The Fortune Hunters The Floating Outfit 12

The Floating Outfit 12 The Hide and Tallow Men (A Floating Outfit Western. Book 7)

The Hide and Tallow Men (A Floating Outfit Western. Book 7) Young Ole Devil

Young Ole Devil Slip Gun

Slip Gun The Drifter

The Drifter The Floating Outfit 45

The Floating Outfit 45 Sidewinder

Sidewinder The Ysabel Kid

The Ysabel Kid Waco 6

Waco 6 Waco 5

Waco 5 Point of Contact

Point of Contact Under the Stars and Bars (A Dusty Fog Civil War Western Book 4)

Under the Stars and Bars (A Dusty Fog Civil War Western Book 4) The Floating Outfit 9

The Floating Outfit 9 Under the Stars and Bars

Under the Stars and Bars .44 Caliber Man

.44 Caliber Man The Floating Outfit 17

The Floating Outfit 17 Ole Devil at San Jacinto (Old Devil Hardin Western Book 4)

Ole Devil at San Jacinto (Old Devil Hardin Western Book 4) The Bloody Border

The Bloody Border A Horse Called Mogollon (Floating Outfit Book 3)

A Horse Called Mogollon (Floating Outfit Book 3) Waco 3

Waco 3 The Texan

The Texan The Floating Outfit 35

The Floating Outfit 35 Mississippi Raider

Mississippi Raider The Big Gun (Dusty Fog's Civil War Book 3)

The Big Gun (Dusty Fog's Civil War Book 3) Goodnight's Dream (A Floating Outfit Western Book 4)

Goodnight's Dream (A Floating Outfit Western Book 4) Waco 4

Waco 4 From Hide and Horn (A Floating Outfit Book Number 5)

From Hide and Horn (A Floating Outfit Book Number 5) The Floating Outfit 18

The Floating Outfit 18 Slaughter's Way (A J.T. Edson Western)

Slaughter's Way (A J.T. Edson Western) Dusty Fog's Civil War 7

Dusty Fog's Civil War 7 Two Miles to the Border (A J.T. Edson Western)

Two Miles to the Border (A J.T. Edson Western) Trigger Fast

Trigger Fast Waco's Badge

Waco's Badge A Matter of Honor (Dusty Fog Civil War Book 6)

A Matter of Honor (Dusty Fog Civil War Book 6) The Half Breed

The Half Breed Bunduki (Bunduki Series Book One)

Bunduki (Bunduki Series Book One) Kill Dusty Fog

Kill Dusty Fog Get Urrea! (An Ole Devil Hardin Western Book 5)

Get Urrea! (An Ole Devil Hardin Western Book 5) Dusty Fog's Civil War 9

Dusty Fog's Civil War 9 The Fastest Gun in Texas (A Dusty Fog Civil War Book 5)

The Fastest Gun in Texas (A Dusty Fog Civil War Book 5) Sagebrush Sleuth (A Waco Western #2)

Sagebrush Sleuth (A Waco Western #2) Quiet Town

Quiet Town Is-A-Man (A J.T. Edson Standalone Western)

Is-A-Man (A J.T. Edson Standalone Western) Rockabye County 5

Rockabye County 5 The Floating Outfit 14

The Floating Outfit 14 Cure the Texas Fever (A Waxahachie Smith Western--Book 3)

Cure the Texas Fever (A Waxahachie Smith Western--Book 3) The Floating Outfit 13

The Floating Outfit 13 The Road to Ratchet Creek

The Road to Ratchet Creek